Wu Ma of Thieves Market

All works by Wu Ma.

This writing was first published on O for Other, a collective blogging project that explores histories, narratives and cultures.

Wu Ma works were featured in Run Amok gallery’s first exhibition, All’s Well, Ends Well / 潮繪,俗畫 in 2013.

Sharon Chin wrote about her encounter with Wu Ma during her visit to George Town in 2014.

How To Be Free: Wu Ma and the Tools of Prolonged Daily Use

This writing was first published on O for Other, a collective blogging project that explores histories, narratives and cultures.

Wu Ma works were featured in Run Amok gallery’s first exhibition, All’s Well, Ends Well / 潮繪,俗畫 in 2013.

Sharon Chin wrote about her encounter with Wu Ma during her visit to George Town in 2014.

How To Be Free: Wu Ma and the Tools of Prolonged Daily Use

As I was tidying up my studio during the current movement control order, I found a pile of paintings by Wu Ma, a self-taught artist who used to run a stall at the Acheen Street (Lebuh Acheh) flea market. Also known locally as the thieves market (Pasar Karat), the Acheen Street flea market was held at the Armenian Park, and extended along Armenian and Acheen Street, usually from the late afternoon till dusk.

Across Armenian street overlooking the park was the restored Penang Islamic Museum. It was an early straits-style bungalow built in 1860 that was once the residence of Syed Mohamed Alatas, a powerful Acehnese pepper merchant who once led the Red Flag secret society and resistance against Dutch hegemony in Acheh. Located at the heart of Penang’s heritage enclave, this al-fresco market was self-organised by the local community where a small token was collected to ensure the park was cleaned up after the market

The last time when I was there, I saw a myriad of random second-hand items on sale such as electronic scraps, clothes, VCDs and DVDs, kitchenware, toys, vintage and antique pieces, old prints, books and magazine; with a pisang goreng and air balang stalls nearby. Most of the items were not priced, and one was expected to haggle. It was never strictly business, many of the stall owners and regulars knew each other. They would often hang under the shade of trees and chat away, or help look after each other’s stall during toilet breaks.

However, in 2015 the park was closed for upgrading work by the local council. And when the park was re-opened in 2017, it was transformed into a quaint modern-looking garden in service of the local residents and tourists. Since then, we lost another vibrant scene of street life in George Town, all in the name of placemaking and urban rejuvenation.

Wu Ma was a regular here. He was usually found in a half lotus sitting position on a sheet of spread-out recycled canvas poster. In front of him was a selection of his paintings, bric-a-brac and small objects of novelty. He was shy when I complimented his paintings but when I asked about the painting material he used, he proudly took out his selection of Buncho poster colours. From the other hand, he produced a bottle of water, poured some of it on the surface of the painting, and upon rubbing on this mixture , pronounced with an air of confidence, “you see, the colours stay”.

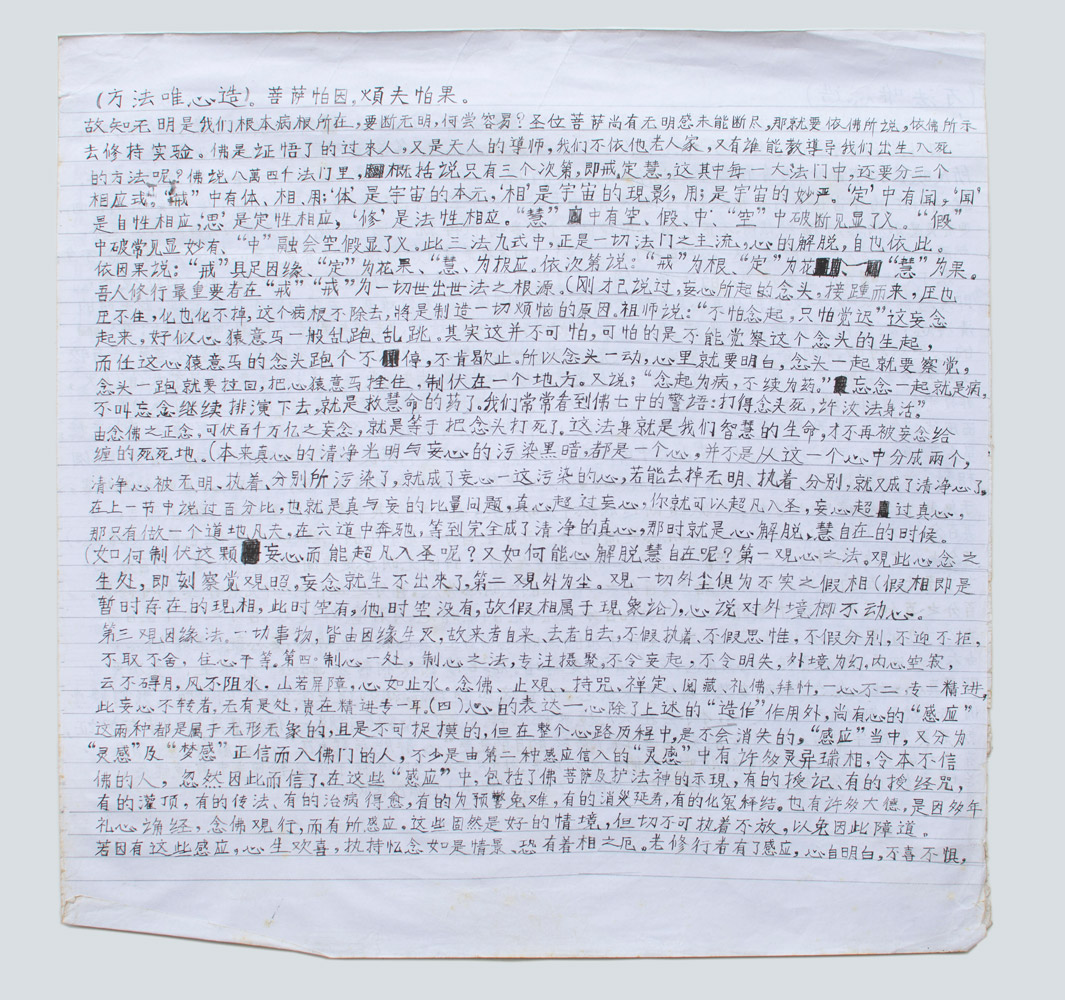

Buncho should consider getting him to endorse their product. With his trusted set of colours, he drew and painted on any scrap of paper he could find or given to him. He also painted on loose sheets of paper including the cardboard of the drawing pads or the back of the calendar.

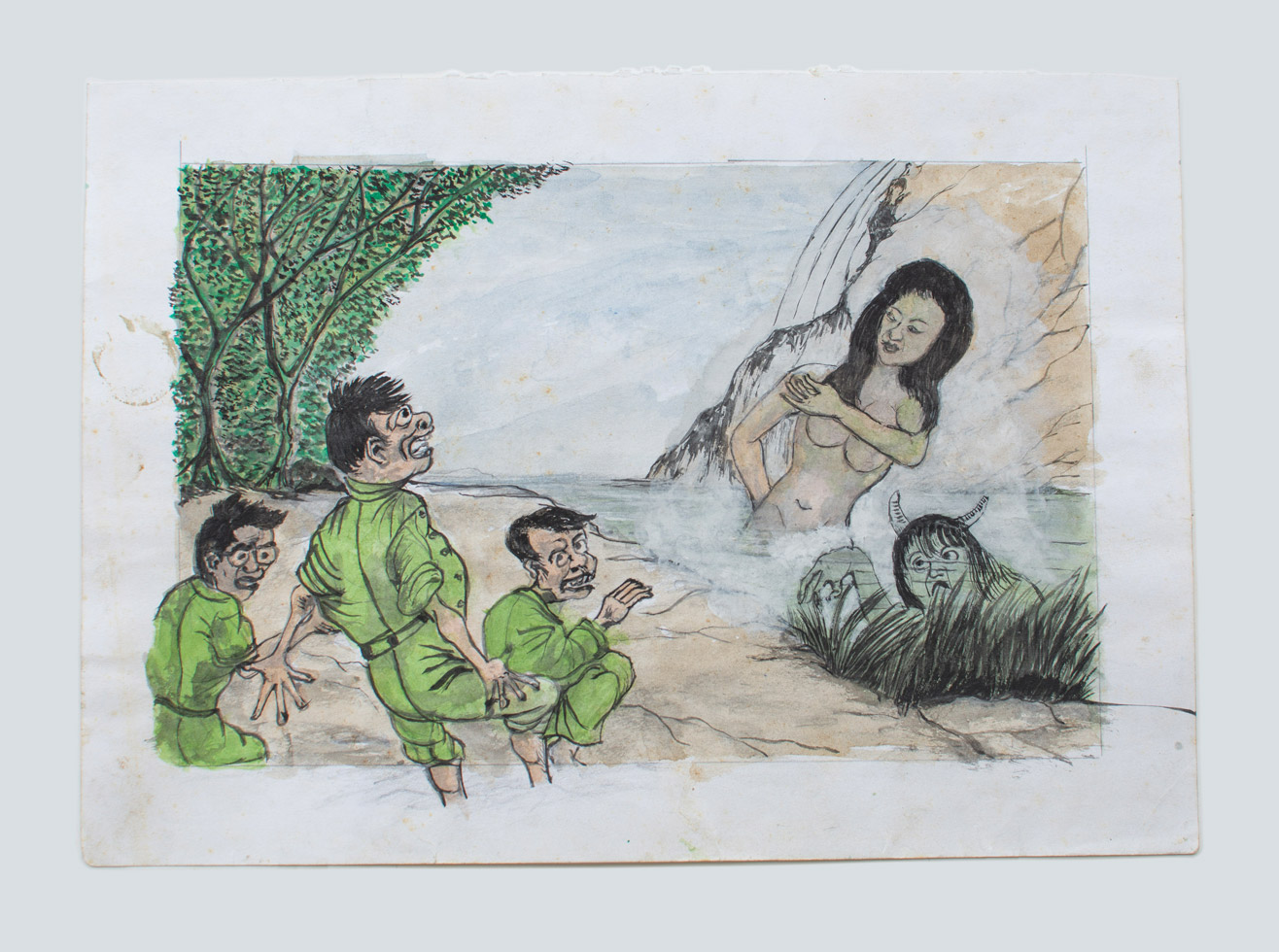

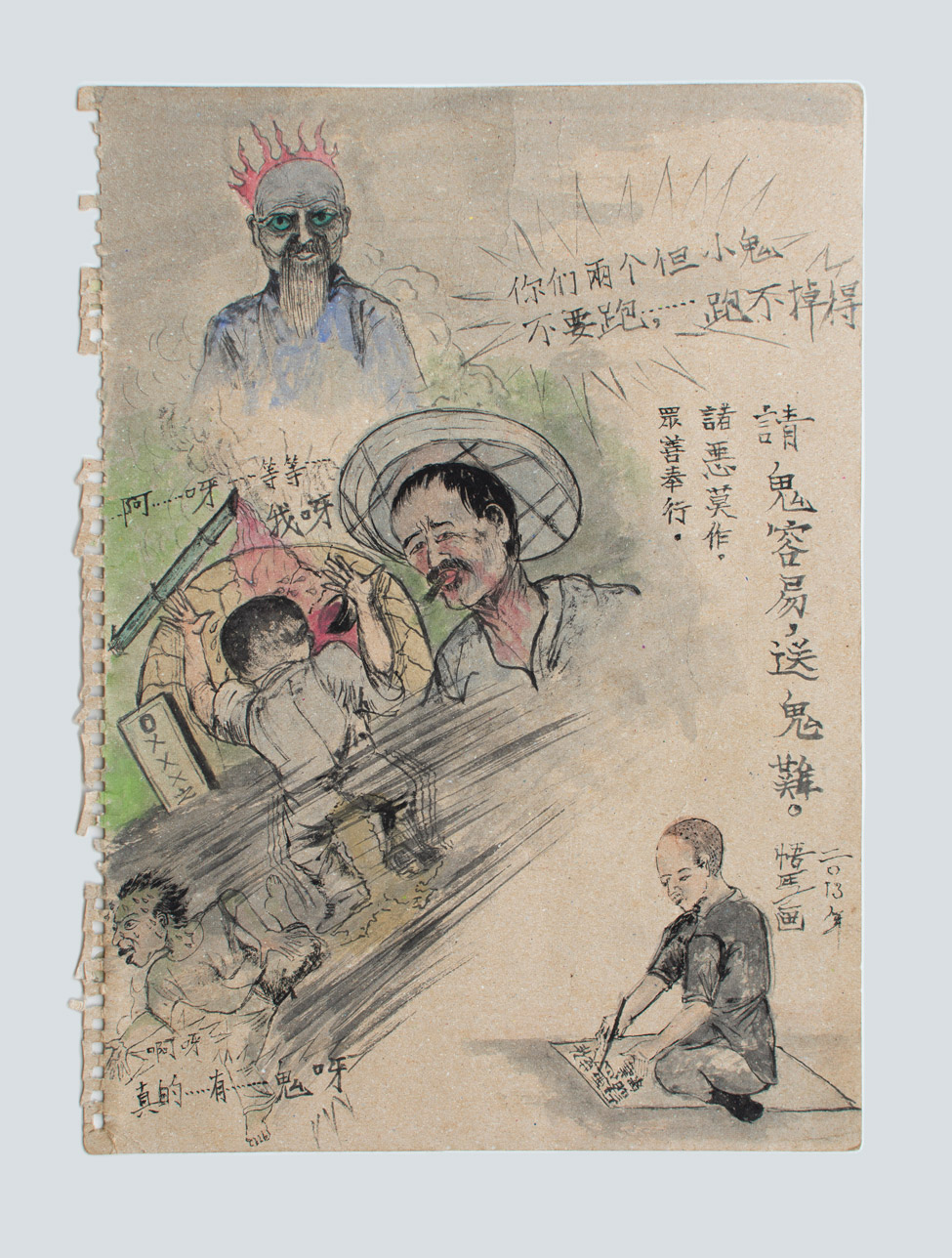

Wu Ma often lamented about his rebellious youth. He would never go into details but often concluded that he was now a devoted Buddhist. He meditated and copied Buddhist aphorism. Some of his paintings carry the ethos of Buddhist teaching, resisting earthly temptations especially the pleasure of sex including his observation on the abuse of trust and power in religious establishments.

Apart from the paintings inspired by Buddhist teachings, painting allowed him to revisit his childhood memories such as how he used to hide behind rocks to peep at couples getting intimate at the beachside in Penang. He used to make paintings of political figureheads but was warned by his peers that he might get into trouble with the authority, and he has stopped since.

Some of his paintings shed light on the unsung heroes like the firefighters, or a local outlaw pirate figure, who stole from the rich to feed the poor. He has a tendency to present women as strong and powerful wrestlers. The marketplace was not short of larger-than-life dramas and his surroundings became a source of inspiration to him. The painting that portrays an angry wife catching her husband looking at a scantily clad woman is an example.

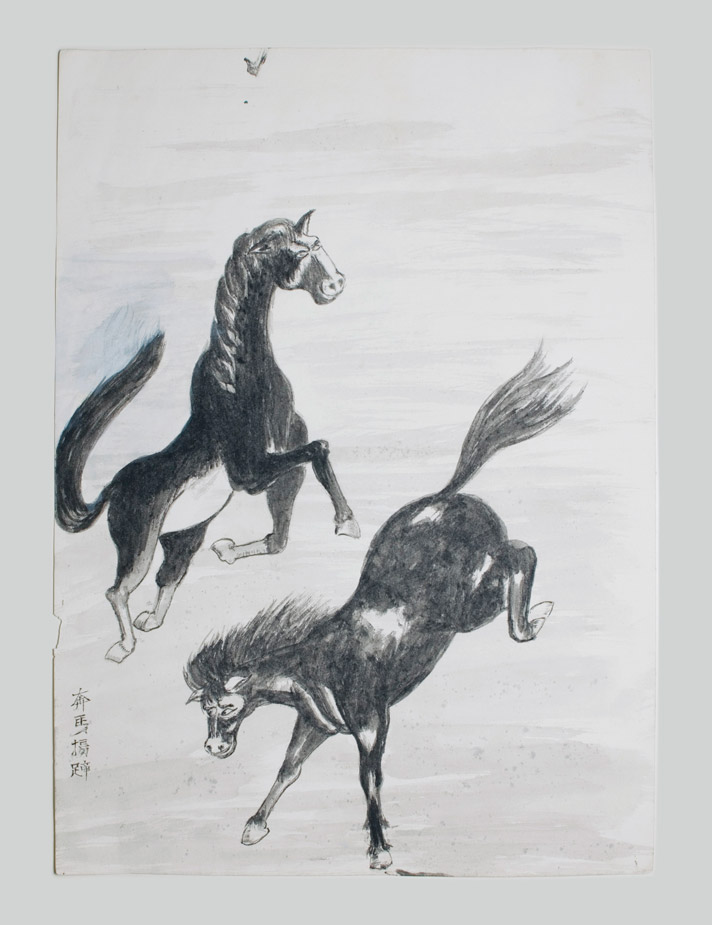

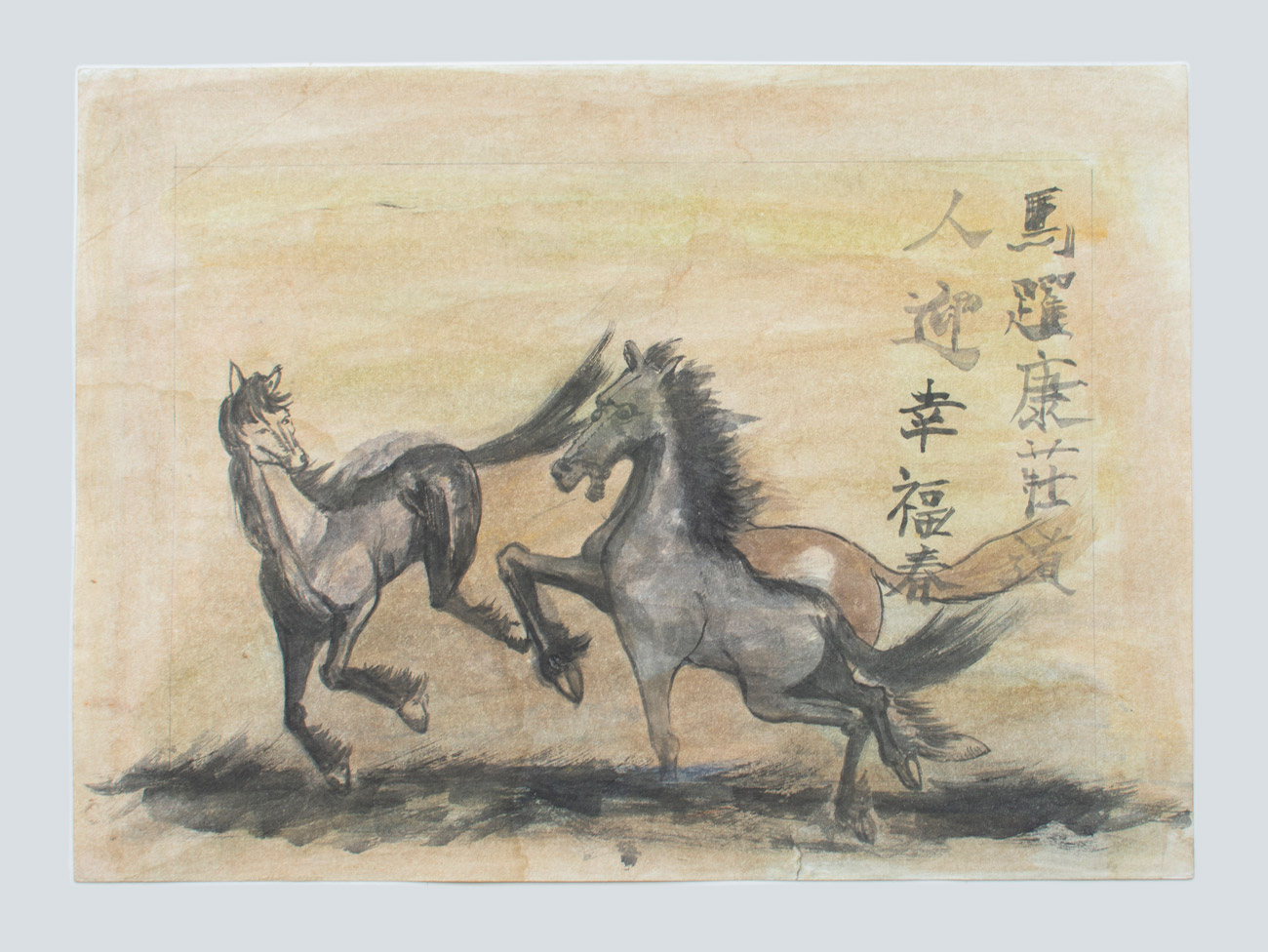

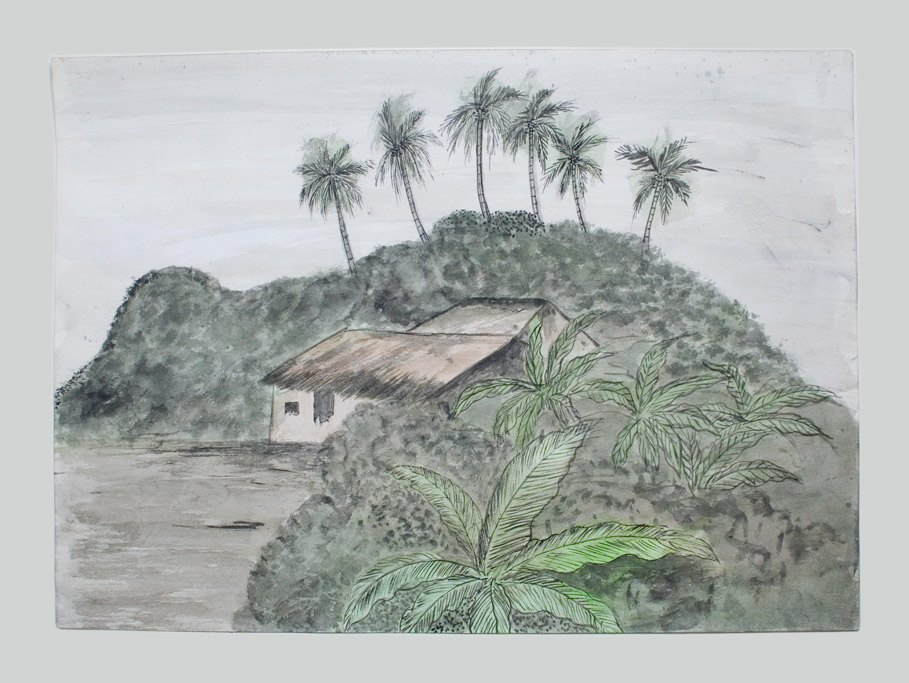

Another series of Wu Ma’s paintings feature cultural symbols typically found in traditional Chinese paintings such as the deities or characters in Chinese mythology, swimming koi fish, Mandarin ducks, galloping horses and landscapes with Pine trees.

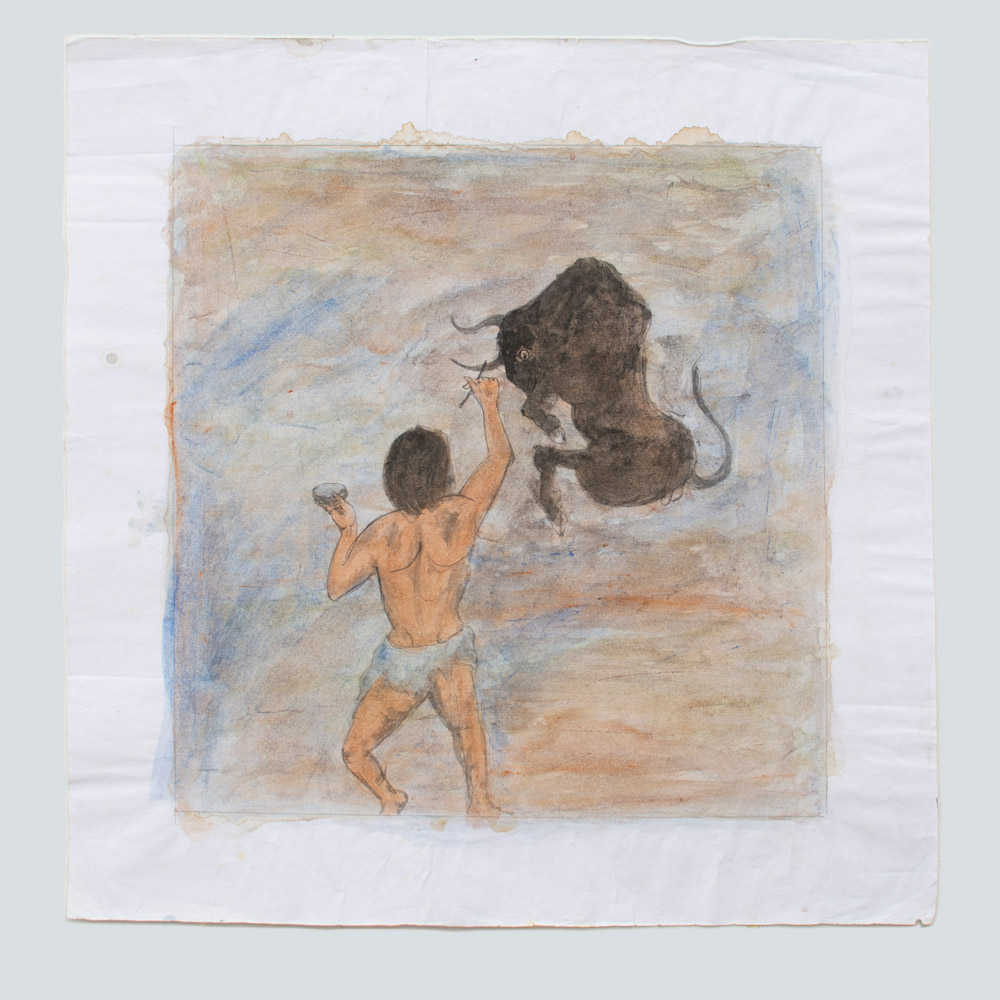

It is hard to tell how much planning or preparation went into his paintings, he sometimes painted on both sides of the paper. Other times, he would paint outside of the frame that he carefully drew to create a border for his pictures. He was also known to change the orientation of his composition mid-way through painting, from a vertical to a horizontal format. Otherwise, figures float in freefall against an empty background.

Wu Ma’s body of work, in general, contains elements that are both lofty and whimsical. On the one hand they resemble illustrations found in the book of virtues or mural painting seen in Buddhist temples. On the other hand, they also remind us of the Old Master Q comic. His grassroots sensibility conveys a spontaneous naivety with the urgency of a courtroom sketcher that reflects on his state of mind, socio-political insights of his daily milieu, spiritual inspirations and cultural upbringing. Painting for Wu Ma is perhaps a means to make ends meet. It is also on some level, a meditative and reflective process. Finally, it is his search for a path towards self-redemption.

If Wu Ma is still alive, he would be 93 this year. I saw less of Wu Ma since Armenian Park’s ‘upgrade’. The last time I saw him was near Beach Street in 2018, parking himself outside a restaurant. He was asking for some drinking water from the waiter. I tried to get his attention but he couldn’t recognise me. He was trying to make himself comfortable by the five-foot-way. I handed him some cash and left. I hope he’s doing alright, especially in times like these.

Across Armenian street overlooking the park was the restored Penang Islamic Museum. It was an early straits-style bungalow built in 1860 that was once the residence of Syed Mohamed Alatas, a powerful Acehnese pepper merchant who once led the Red Flag secret society and resistance against Dutch hegemony in Acheh. Located at the heart of Penang’s heritage enclave, this al-fresco market was self-organised by the local community where a small token was collected to ensure the park was cleaned up after the market

The last time when I was there, I saw a myriad of random second-hand items on sale such as electronic scraps, clothes, VCDs and DVDs, kitchenware, toys, vintage and antique pieces, old prints, books and magazine; with a pisang goreng and air balang stalls nearby. Most of the items were not priced, and one was expected to haggle. It was never strictly business, many of the stall owners and regulars knew each other. They would often hang under the shade of trees and chat away, or help look after each other’s stall during toilet breaks.

However, in 2015 the park was closed for upgrading work by the local council. And when the park was re-opened in 2017, it was transformed into a quaint modern-looking garden in service of the local residents and tourists. Since then, we lost another vibrant scene of street life in George Town, all in the name of placemaking and urban rejuvenation.

Wu Ma was a regular here. He was usually found in a half lotus sitting position on a sheet of spread-out recycled canvas poster. In front of him was a selection of his paintings, bric-a-brac and small objects of novelty. He was shy when I complimented his paintings but when I asked about the painting material he used, he proudly took out his selection of Buncho poster colours. From the other hand, he produced a bottle of water, poured some of it on the surface of the painting, and upon rubbing on this mixture , pronounced with an air of confidence, “you see, the colours stay”.

Buncho should consider getting him to endorse their product. With his trusted set of colours, he drew and painted on any scrap of paper he could find or given to him. He also painted on loose sheets of paper including the cardboard of the drawing pads or the back of the calendar.

Wu Ma often lamented about his rebellious youth. He would never go into details but often concluded that he was now a devoted Buddhist. He meditated and copied Buddhist aphorism. Some of his paintings carry the ethos of Buddhist teaching, resisting earthly temptations especially the pleasure of sex including his observation on the abuse of trust and power in religious establishments.

Apart from the paintings inspired by Buddhist teachings, painting allowed him to revisit his childhood memories such as how he used to hide behind rocks to peep at couples getting intimate at the beachside in Penang. He used to make paintings of political figureheads but was warned by his peers that he might get into trouble with the authority, and he has stopped since.

Some of his paintings shed light on the unsung heroes like the firefighters, or a local outlaw pirate figure, who stole from the rich to feed the poor. He has a tendency to present women as strong and powerful wrestlers. The marketplace was not short of larger-than-life dramas and his surroundings became a source of inspiration to him. The painting that portrays an angry wife catching her husband looking at a scantily clad woman is an example.

Another series of Wu Ma’s paintings feature cultural symbols typically found in traditional Chinese paintings such as the deities or characters in Chinese mythology, swimming koi fish, Mandarin ducks, galloping horses and landscapes with Pine trees.

It is hard to tell how much planning or preparation went into his paintings, he sometimes painted on both sides of the paper. Other times, he would paint outside of the frame that he carefully drew to create a border for his pictures. He was also known to change the orientation of his composition mid-way through painting, from a vertical to a horizontal format. Otherwise, figures float in freefall against an empty background.

Wu Ma’s body of work, in general, contains elements that are both lofty and whimsical. On the one hand they resemble illustrations found in the book of virtues or mural painting seen in Buddhist temples. On the other hand, they also remind us of the Old Master Q comic. His grassroots sensibility conveys a spontaneous naivety with the urgency of a courtroom sketcher that reflects on his state of mind, socio-political insights of his daily milieu, spiritual inspirations and cultural upbringing. Painting for Wu Ma is perhaps a means to make ends meet. It is also on some level, a meditative and reflective process. Finally, it is his search for a path towards self-redemption.

If Wu Ma is still alive, he would be 93 this year. I saw less of Wu Ma since Armenian Park’s ‘upgrade’. The last time I saw him was near Beach Street in 2018, parking himself outside a restaurant. He was asking for some drinking water from the waiter. I tried to get his attention but he couldn’t recognise me. He was trying to make himself comfortable by the five-foot-way. I handed him some cash and left. I hope he’s doing alright, especially in times like these.